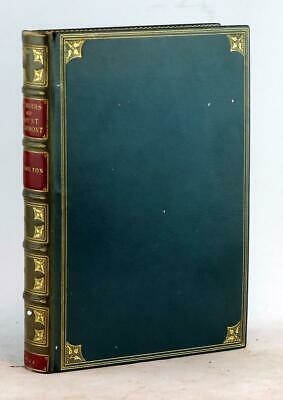

The first book is addressed to the reader, where Montaigne declares that he did not seek fame and did not seek to benefit - this is primarily a “sincere book”, and it is intended for relatives and friends so that they can revive in memory his appearance and character when he arrives the time for separation is already very close.

Book I

Chapter 1. One can achieve the same thing in different ways.

Amazingly bustling, truly unstable and ever-vacillating creature - a man.

The ruler’s heart can be tempered by submission. But there are examples when directly opposite qualities - courage and hardness - led to the same result. So, Edward, Prince of Wales, capturing Limoges, remained deaf to the pleas of women and children, but spared the city, admiring the courage of three French nobles. Emperor Conrad III forgave the defeated Duke of Bavaria when noble ladies carried their own husbands from the besieged fortress on their shoulders. Montaigne says about himself that he could be influenced by both ways, but by nature he is so inclined to mercy that he would rather be disarmed by pity, although the Stoics consider this feeling worthy of condemnation.

Chapter 14. The fact that our perception of good and evil largely depends on the idea that we have about them

Anyone who suffers for a long time is to blame for this himself.

Suffering is caused by reason. People see death and poverty as their worst enemies; Meanwhile, there are many examples when death was the highest good and the only refuge. It happened more than once that a person maintained the greatest presence of spirit in the face of death and, like Socrates, drank for the health of his friends. When Louis XI captured Arras, many were hanged for refusing to shout "Long live the king!" Even such low souls as jesters do not give up joking before execution. And if it comes to beliefs, then they are often defended at the cost of life, and each religion has its own martyrs - for example, during the Greek-Turkish wars, many chose to die a painful death, so as not to undergo the rite of baptism. It is reason that fears death, for it is only a moment that separates it from life. It is easy to see that the power of the mind exacerbates the suffering — the surgeon’s razor incision is felt more than the sword strike received in the heat of battle. And women are ready to endure incredible torment, if they are sure that this will benefit their beauty - everyone heard about a Parisian lady who ordered her skin torn off in the hope that the new one would take on a fresher look. The concept of things is a great power. Alexander the Great and Caesar strove for dangers with much greater zeal than others for security and peace. Not need, but abundance breeds greed in people. Montaigne was convinced of the validity of this statement from his own experience. Until about twenty years, he lived with only occasional means - but he spent the money merrily and carefreely. Then he had savings, and he began to put off the surplus, having lost peace of mind in return. Fortunately, some kind genius knocked out all this nonsense from his head, and he completely forgot about skopidomstvo - and now lives in a pleasant, orderly way, balancing his income with expenses. Anyone can do the same, because everyone lives well or badly depending on what he thinks about it, and there is nothing to help a person if he does not have the courage to endure death and endure life.

Book II

Chapter 12. Apology of Raimund Sabundsky

The saliva of the lousy cur, splashing Socrates's hand, can destroy all his wisdom, all his great and thoughtful ideas, destroy them completely, leaving no trace of his former knowledge.

Man ascribes great power to himself and imagines himself the center of the universe. So a stupid gosling could reason, believing that the sun and stars shine only for him, and people were born to serve him and care for him. By the vanity of the imagination, man equates himself with God, while he lives in the midst of dust and sewage. At any moment, death awaits him, to fight with which he is not capable. This miserable creature is not even able to control himself, but he longs to command the universe. God is completely incomprehensible to the grain of reason that man possesses. Moreover, the reason is not given to embrace the real world, because everything in it is impermanent and changeable. And in terms of perception, man is even inferior to animals: some surpass him in sight, others in hearing, and others in sense of smell. Perhaps a person is generally devoid of several feelings, but does not suspect this of his ignorance. In addition, abilities depend on bodily changes: for a patient, the taste of wine is not the same as for a healthy one, but numb fingers can perceive the hardness of a tree differently. Sensations are largely determined by changes and moods - in anger or joy the same feeling can manifest itself in different ways. Finally, estimates change over time: what seemed to be true yesterday is now considered false, and vice versa. Montaigne himself had more than once been able to maintain an opinion contrary to his own, and he found such convincing arguments that he abandoned his previous judgment. In his own writings, he sometimes cannot find the original meaning, guesses about what he wanted to say, and makes amendments that may spoil and distort the idea. So the mind either stomps on the spot, or wanders and rushes about, finding no way out.

Chapter 17. On Doubt

Everyone peers at what is before him; I peer at myself.

People create for themselves an exaggerated concept of their virtues - it is based on reckless self-love. Of course, one should not belittle oneself, for the verdict must be fair, Montaigne notes a tendency to downplay the true value of his property and, on the contrary, exaggerate the value of everything else. He is seduced by the polity and customs of distant peoples. Latin, for all its merits, inspires more reverence than it deserves. Having successfully dealt with some business, he attributes it more to luck than to his own skill. Therefore, even among the statements of the ancients about man, he most readily accepts the most irreconcilable, believing that the purpose of philosophy is to expose human conceit and vanity. He considers himself to be a mediocre person, and his only difference from others is that he clearly sees all his shortcomings and does not come up with excuses for them. Montaigne is envious of those who are able to rejoice at the work of their hands, for his own writings cause only annoyance in him. The French language is rough and careless, and the Latin, which he once possessed in perfection, lost its former luster. Any story becomes dry and dull under his pen - he does not have the ability to amuse or encourage imagination. Likewise, his own appearance does not satisfy him, and yet beauty is a great force that helps in communication between people. Aristotle writes that Indians and Ethiopians, when choosing kings, always paid attention to growth and beauty - and they were absolutely right, for the tall, powerful leader inspires reverence in his subjects, and frightens the enemies. Montaigne is not satisfied with his spiritual qualities, reproaching himself primarily for laziness and heaviness. Even those traits of his character that cannot be called bad are completely useless in this century: compliance and complaisance will be called weakness and cowardice, honesty and conscientiousness will be considered absurd scrupulousness and prejudice. However, there are some advantages in ruined times, when it is prayed without special effort to become the embodiment of virtue: whoever does not kill his father and does not rob churches is already a decent and perfectly honest man. Next to the ancient Montaigne, he seems to himself a pygmy, but in comparison with the people of his age, he is ready to admit unusual and rare qualities, for he would never give up his convictions for the sake of success and has a fierce hatred of the new-fashioned virtue of pretense. In communicating with those in power, he prefers to be bothersome and immodest than a flatterer and pretender, since he does not have a flexible mind to wiggle when asked directly, and his memory is too weak to hold a distorted truth - in a word, this can be called courage from weaknesses. He knows how to defend certain views, but is absolutely not able to choose them - after all, there are always many arguments in favor of any opinion. Nevertheless, he does not like to change his mind, because in opposite judgments he seeks out the same weaknesses. And he appreciates himself for something that others will never admit, since no one wants to be considered stupid, his judgments about himself are ordinary and old as the world. Everyone is waiting for praise for the liveliness and speed of mind, but Montaigne prefers to be praised for the severity of opinions and morals.

Book III

Chapter 13. About the experience

There is nothing more beautiful and worthy of approval than properly fulfilling your human purpose.

There is no more natural desire than the desire to acquire knowledge. And when there is a lack of ability to think, a person turns to experience. But the endless variety and variability of things. For example, in France there are more laws than in the rest of the world, but this only leads to the fact that the possibilities for arbitrariness have expanded infinitely - it would be better to have no laws at all than such an abundance. And even the French language, so convenient in all other cases of life, becomes dark and obscure in treaties or wills. In general, from many interpretations, the truth seems to be fragmented and scattered. The wisest laws are established by nature, and it should be trusted in the simplest way - in essence, there is nothing better than ignorance and unwillingness to know. It is preferable to understand yourself well than Cicero. There are not as many instructive examples in Caesar's life as in our own. Apollo, the god of knowledge and light, inscribed on the pediment of his temple the call “Know thyself” - and this is the most comprehensive advice he could give people. Studying himself, Montaigne learned to understand other people pretty well, and his friends were often amazed that he understands their life circumstances much better than themselves. But there are few people who can listen to the truth about themselves without being offended or offended. Montaigne was sometimes asked what activity he feels fit for, and he sincerely replied that he was not fit for anything. And even rejoiced at this, because he could not do anything that could turn him into a slave to another person. However, Montaigne would be able to tell his master the truth about himself and describe his temper, in every way refuting flatterers. For the rulers are endlessly spoiled by the scum surrounding them - even Alexander, the great sovereign and thinker, was completely defenseless before flattery. In the same way, Montaigne’s experience is extremely useful for the health of the body, since it appears in a pure form, not spoiled by medical contrivances. Tiberius quite rightly asserted that after twenty years everyone should understand what is harmful to him and what is useful, and, therefore, do without doctors. The patient should adhere to the usual lifestyle and his usual food - sudden changes are always painful. We must reckon with our desires and inclinations, otherwise one trouble will have to be treated with the help of another. If you drink only spring water, if you deprive yourself of movement, air, light, is life worth such a price? People tend to believe that only the unpleasant is useful, and everything that is not painful seems suspicious to them. But the body itself makes the right decision. In his youth, Montaigne loved hot seasonings and sauces, when they began to harm the stomach, he immediately stopped loving them. Experience teaches that people destroy themselves with impatience, meanwhile, diseases have a strictly defined fate, and they are also given a certain term. Montaigne completely agrees with Krantor that one should neither recklessly resist the disease, nor surrender to it unwittingly - let it follow the natural course, depending on its own and human properties. And the mind will always come to the rescue: for example, he inspires Montaigne that kidney stones are just a tribute to old age, because it is time for all organs to weaken and deteriorate. In fact, the befallen Montaigne punishment is very soft - this is truly a fatherly punishment. She came late and tormented at an age that in itself is barren. There is one more advantage in this disease - there is no need to guess about anything, while other ailments are pestering with anxiety and excitement due to unclear reasons. Let the large stone torment and tear the kidney tissue, let life and blood flow out a little with urine, as unnecessary and even harmful sewage, - at the same time, you can experience something like a pleasant feeling. No need to be afraid of suffering, otherwise you have to suffer from the fear itself. When thinking about death, the main consolation is that this phenomenon is natural and fair - who dares to demand mercy for himself in this regard? Everything should be taken as an example from Socrates, who knew how to calmly endure hunger, poverty, disobedience of children, the evil temper of his wife, and in the end he accepted slander, oppression, prison, fetters and poison.