The meeting of the Kazan landowner Vasily Ivanovich, burly, thorough and middle-aged, with Ivan Vasilyevich, thin, dapper, barely arrived from abroad - this meeting, which happened on Tversky Boulevard, was very fruitful. Vasily Ivanovich, gathering back to his estate in Kazan, invites Ivan Vasilyevich to take him to his father's village, which for Ivan Vasilyevich, who was very costly abroad, is very helpful. They set off in a tarantass, a bizarre, awkward, but rather convenient construction, and Ivan Vasilyevich, assuming the goal of studying Russia, takes with him a solid notebook, which he intends to fill with travel impressions.

Vasily Ivanovich, confident that they are not traveling, but simply traveling from Moscow to Mordasy via Kazan, is somewhat puzzled by the enthusiastic intentions of his young companion, who on the way to the first station outlines his tasks, briefly touching on the past, future and present of Russia, condemns the bureaucracy, courtyard serfs and the Russian aristocracy.

However, the station replaces the station, not giving Ivan Vasilyevich fresh impressions. There are no horses on each, everywhere Vasily Ivanovich revels in tea, everywhere he has to wait for hours. Along the way, dormant travelers cut off a couple of suitcases and several boxes with gifts for the wife of Vasily Ivanovich. Saddened, tired of shaking, they hope to rest in a decent Vladimir hotel (Ivan Vasilyevich suggests that Vladimir open his travel notes), but in Vladimir they will have a bad dinner, a room without bedding, so that Vasily Ivanovich sleeps on his feather bed, and Ivan Vasilyevich on brought hay, from which an indignant cat jumps out. Suffering from fleas, Ivan Vasilyevich sets out to his companion in misfortune his views on the arrangement of hotels in general and their public benefit, and also tells what hotel in the Russian spirit he wanted to arrange, but Vasily Ivanovich did not heed, for he was sleeping.

In the early morning, leaving the sleeping Vasily Ivanovich in the hotel, Ivan Vasilievich leaves for the city. The requested bookseller is ready to hand him the “Views of the Provincial City”, and almost for nothing, but not of Vladimir, but of Constantinople. An independent acquaintance of Ivan Vasilievich with the sights tells him little, and an unexpected meeting with a long-time boarding friend, Fedey, distracts from thinking about true antiquity. Fedya tells the “simple and stupid story” of his life: how he went to serve in St. Petersburg, how, having no habit of zeal, could not advance his service, and therefore soon got bored with it, how, forced to lead a life characteristic of his circle, he went bankrupt, how yearned, married, discovered that his wife’s condition was even more upset, and could not leave Petersburg, because his wife was used to walking along Nevsky, as old acquaintances began to neglect him, having heard about his difficulties. He left for Moscow and fell into a society of idleness from the bustle society, played, lost, was a witness, and then a victim of intrigue, stood up for his wife, wanted to shoot, and now he was expelled to Vladimir. The wife returned to her father in Petersburg. Saddened by the story, Ivan Vasilievich hurries to the hotel, where Vasily Ivanovich is already looking forward to it.

At one of the stations, he thinks in the usual expectation of where to look for Russia, since there are no antiquities, there are no provincial societies, and the capital’s life is borrowed. The innkeeper reports that there are gypsies outside the city, and both travelers, enthusiastic, set off for the camp. Gypsies are dressed in European dirty dresses and instead of nomadic songs they sing vaudeville Russian romances - a book of travel impressions falls out of the hands of Ivan Vasilyevich. Returning, the owner of the inn, accompanying them, tells why he had to once sit in a prison - the story of his love for the wife of a private bailiff was set out right here.

Continuing their movement, travelers miss, yawn and talk about literature, whose current position does not suit Ivan Vasilyevich, and he exposes its venality, its imitation, its oblivion of its folk roots, and when inspired, Ivan Vasilievich gives the literature several sensible and simple recipes for recovery , he discovers his listener asleep. Soon, in the middle of the road, they meet a carriage with a bursting spring, and in a scolding bad words, Mr. Ivan Vasilyevich is amazed to recognize his acquaintance in Paris, a certain prince. He, as long as the people of Vasily Ivanovich participate in the repair of his crew, announces that he is going to the village for arrears, scolding Russia, reports the latest gossip from Paris, Roman and other lives and is rapidly departing. Our travelers, reflecting on the oddities of the Russian nobility, come to the conclusion that the past is wonderful past, and the future in Russia - the tarantas, meanwhile, is approaching Nizhny Novgorod.

Since Vasily Ivanovich, rushing to Mordasy, will not stop here, the author takes over the description of the Lower, and especially of his Pechora monastery. Vasily Ivanovich describes his companions about the hardships of landlord life in detail, describes it, sets out his views on peasant farming and landlord administration, and at the same time shows such a note, prudence and truly fatherly participation that Ivan Vasilievich is filled with reverent respect for him.

Arriving by the evening of the next day in a contingent town, travelers are amazed to find a breakdown in the tarantass and, leaving it in the care of a blacksmith, go to the tavern, where, after ordering tea, three merchants, gray, black and red, listen to the conversation. A fourth appears and hands over five thousand to a gray-haired man with a request to transfer money to someone in Rybna, where he goes. Having entered into the questions, Ivan Vasilyevich learns with amazement that the guarantor of the gray-haired man is not a relative, he is not even really familiar, but he did not take any receipts. It turns out that, completing millions of cases, their merchants carry out calculations on shreds, on the road they carry all the money with them, in their pockets. Ivan Vasilievich, having his own idea of trade, talks about the need for science and the system in this important matter, about the merits of enlightenment, about the importance of combining mutual efforts for the good of the fatherland. The merchants, however, do not too grasp the meaning of his eloquent tirade.

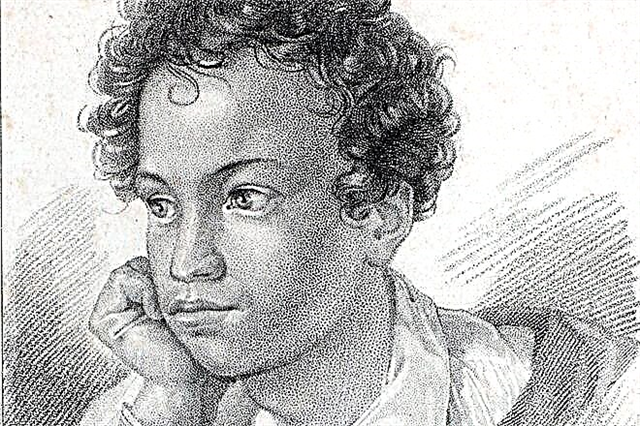

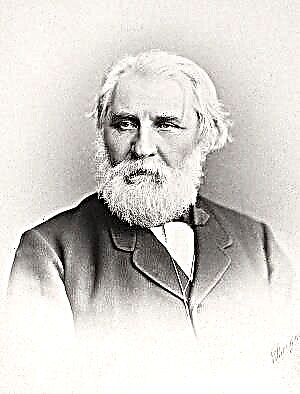

After parting with the merchants, the author hurries to finally acquaint the reader with Vasily Ivanovich closer and tells the story of his life: a childhood spent on a dovecot, drunken father Ivan Fedorovich, who surrounded himself with fools and jesters, mother Arina Anikimovna, serious and stingy, learning from the clerk, then home teacher, service in Kazan, meeting with Avdotya Petrovna at the ball, refusal of harsh parents to bless this marriage, patient three-year expectation, another year of mourning for the deceased father and finally the long-awaited marriage, moving to the village, starting a farm, giving birth to children. Vasily Ivanovich eats a lot and eagerly and is completely satisfied with everything: his wife and life. Leaving Vasily Ivanovich, the author proceeds to Ivan Vasilyevich, narrates about his mother, the princess of Moscow, a frantic Frenchwoman who replaced Moscow with Kazan during the coming of the French. Over time, she married some dumb landowner who looked like a marmot, and from this marriage was born Ivan Vasilievich, who grew up under the tutelage of a completely ignorant French governor. Remaining completely unaware of what was happening around him, but firmly knowing that the first poet Rasin, Ivan Vasilyevich, after his mother’s death, was sent to a private St. Petersburg boarding house, where he became a hangover, lost all knowledge and failed at the final exam. Ivan Vasilievich rushed to serve, imitating his more zealous comrades, but the business that was started with enthusiasm soon bored him. He fell in love, and his chosen one, even answering him in kind, suddenly married a rich freak. Ivan Vasilyevich plunged into secular life, but was bored with it, he sought solace in the world of poetry, science seemed tempting to him, but ignorance and restlessness always turned out to be an obstacle. He went abroad, wanting to dissipate and enlighten at the same time, and there, noting that many pay attention to him only because he is Russian, and that all eyes are involuntarily turned to Russia, he suddenly thought about Russia himself and hurried into it already the intention known to the reader.

Reflecting on the need to find a nationality, Ivan Vasilievich enters the village. The village has a chrome holiday. He observes various pictures of drunkenness, from the young women he receives the insulting nickname of a “licked German”, having discovered a schismatic, he tries to find out what is the attitude of the villagers to heresies and meets with complete misunderstanding. The next day, Ivan Vasilievich in the hut of the station superintendent discovers an official who is acting as a police officer and is now waiting for the governor visiting the province. Vasily Ivanovich, loving new acquaintances, sits down with him at the seagulls. There follows a conversation during which Ivan Vasilievich tries to convict the official of requisitions and bribes, but it turns out that now the time is not that the official’s position is the most poor, he is old, weak. To complete the sad picture, Ivan Vasilyevich discovers behind a curtain of a paralyzed caretaker surrounded by three children, the eldest performs his father's duties, and the caretaker dictates to him what to write on the road.

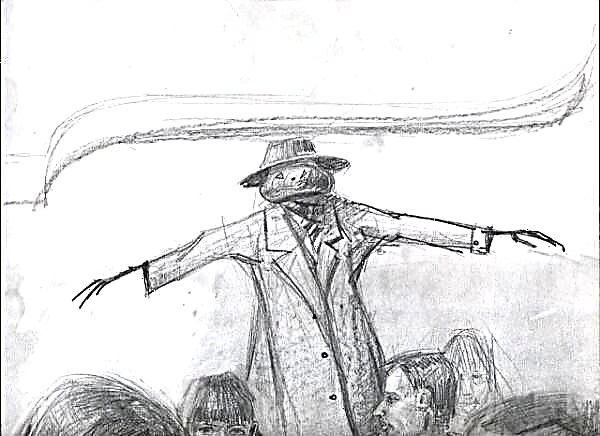

Approaching Kazan, Ivan Vasilievich is somewhat animated, for he decides to write a short but expressive chronicle of Eastern Russia; his fervor, however, soon subsides, as one would expect: his search for sources frightens him. He is considering whether to write a statistical article or an article about the local university (and about all universities in general), or about manuscripts in the local library, or to study the influence of the East on Russia, moral, commercial and political. At this time, the hotel room, in which Ivan Vasilievich indulges in dreams, is filled with Tatars offering a Khan's bathrobe, turquoise, Chinese pearls and Chinese mascara. Waking up soon, Vasily Ivanovich inspects purchases, announces the real price of each item purchased at exorbitant prices, and, to the horror of Ivan Vasilyevich, orders to lay a tarantass. In the middle of a gathering night, moving along the bare steppe in an unchanged tarantass, Ivan Vasilievich sees a dream. He dreams of the amazing transformation of a tarantass into a bird and a flight through some stuffy and gloomy cave filled with terrible shadows of the dead; terrible hellish visions give way to one another, threatening the terrified Ivan Vasilyevich. Finally, the tarantass flies out into the fresh air, and the pictures of a beautiful future life are revealed: both transformed cities and strange flying crews. Tarantas descends to the ground, losing its essence as a bird, and rushes through marvelous villages to a renewed and unrecognizable Moscow. Here, Ivan Vasilievich sees the prince, recently met on the road - he is in a Russian suit, reflects on the independent path of Russia, its God's chosen people and his civic duty.

Then Ivan Vasilyevich meets Fedya, his recent Vladimir interlocutor, and leads him to his modest home. There, Ivan Vasilievich sees his beautiful, serene wife with two charming babies, and, touched by his soul, he suddenly finds himself, and together with Vasily Ivanovich, in the mud, under an overturned tarantass.

Marianne's Life

Marianne's Life