Once, seven peasants - recent serfs, and now temporarily liable "from adjacent villages - Zaplatov, Dyryavin, Razutov, Znobishin, Gorelov, Neyelov, Neurozhayka identity" converge on a highway. Instead of going their own way, men are engaging in a debate about who lives in Russia cheerfully and freely. Each of them judges in his own way who the main lucky man in Russia is: a landowner, an official, a priest, a merchant, a noble nobleman, a minister of sovereign or a tsar.

Behind the argument, they do not notice that they gave a thirty-mile hook. Seeing that it’s too late to return home, the men make a fire and continue to argue over vodka - which, of course, gradually develops into a fight. But the fight does not help to resolve the question that excites men.

The solution is unexpected: one of the men, Groin, catches a baby bird, and in order to free the baby bird, the baby tells the guys where to find a tablecloth. Now the peasants are provided with bread, vodka, cucumbers, kvask, tea - in a word, everything that they need for a long trip. And besides, a self-made tablecloth will mend and wash their clothes! Having received all these benefits, the men give the vow to find out, "whoever has fun, freely in Russia."

The first possible “lucky man” he met along the way is pop. (It wasn’t for the soldiers and beggars they met to ask about happiness!) But the priest’s answer to the question of whether his life is sweet disappoints men. They agree with the priest that happiness is at rest, wealth and honor. But the pop does not possess any of these benefits. In haymaking, in stubble, in the dead of autumn night, in severe frost, he must go to where there are sick, dying and born. And every time his soul hurts at the sight of tombstones and orphan sorrow - so that his hand does not rise to take the copper nickels - a miserable retribution for the demand. The landlords, who had previously lived in family estates and were married here, baptized the children, buried the dead, are now scattered not only in Russia, but also in distant foreign lands; one cannot hope for their retribution. But the men themselves know about the priest's honor: they feel embarrassed when the priest blames obscene songs and insults to the priests.

Realizing that Russian pop is not one of the lucky ones, men go to a festive fair in the trading village of Kuzminskoye to ask people about happiness there. In a rich and dirty village there are two churches, a tightly boarded up house with the inscription "school", a feldsher's hut, a dirty hotel. But most of all in the village are drinking establishments, in each of which they barely manage to cope with the thirsty. The old man Vavila cannot buy goggle shoes for her granddaughter, because he was drunk to a penny. It is good that Pavlusha Veretennikov, a lover of Russian songs, whom everyone for some reason is called "master", buys for him the coveted hotel.

The wanderer men watch the booth Petrushka, watch the offeni pick up the book goods - but by no means Belinsky and Gogol, but portraits of fat generals who are not known to anyone and works about the “stupid milord”. They also see how a brisk trading day ends: rampant drunkenness, fights on the way home. However, the men are outraged by the attempt of Pavlusha Veretennikov to measure the peasant by the master’s measure. In their opinion, it is impossible to live in a sober person in Russia: he will not endure either overwork or peasant misfortune; without a drink, a bloody rain would have spilled from the angry peasant soul. These words are confirmed by Yakim Nagoy from the village of Bosovo - one of those who "works to death, drinks to death." Yakim believes that only pigs walk on the earth and do not see the sky for ages. During the fire, he himself did not save money accumulated over his whole life, but useless and beloved little pictures hanging in a hut; he is sure that with the cessation of drunkenness, great sadness will come to Russia.

The peasant wanderers do not lose hope of finding people who live well in Russia. But even for the promise of the gift of water for the lucky, they fail to find such. For the sake of gratuitous drinks, a torn worker and a former courtyard, paralyzed by a paralysis, who licked plates with the best French truffle from the master for forty years, and even tattered beggars, are ready to announce themselves lucky.

Finally, someone tells them the story of Yermil Girin, a burmister in the estate of Prince Yurlov, who earned universal respect for his justice and honesty. When Jirin needed the money to buy the mill, the men lent it to him without even requiring a receipt. But Yermil is now unhappy: after a peasant riot, he sits in prison.

About the misfortune that befell the nobility after the peasant reform, tells the peasant wanderers the rosy sixty-year-old landowner Gavril Obolt-Obolduev. He recalls how in the old days everything was amused by the master: villages, forests, cornfields, serf actors, musicians, hunters, who belonged to him completely. Obolt-Obolduyev with emotion talks about how, on twelfth holidays, he invited his serfs to pray in the manor house - despite the fact that after that it was necessary to drive away women from all the patrimony to wash the floors.

Although the peasants themselves know that life in serfdom was far from an idyll drawn by Obolduev, they nevertheless understand that the great chain of serfdom, having broken, struck both the gentleman, who at once lost his usual way of life, and the peasant.

Desperate to find a happy man among the men, the wanderers decide to ask the women. Nearby peasants recall that Matrena Timofeevna Korchagina, who everyone considers lucky, lives in the village of Klin. But Matryona herself thinks differently. In confirmation, she tells the wanderers the story of her life.

Prior to marriage, Matrona lived in a non-drinking and prosperous peasant family. She married the stove-maker from the alien village of Philip Korchagin. But the only happy night was for her, when the groom persuaded Matryona to marry him; then began the usual hopeless life of a village woman. True, her husband loved her and beat her only once, but he soon went to work in St. Petersburg, and Matryona was forced to endure resentment in the family of her father-in-law. The only one who felt sorry for Matren was Grandfather Savely, who lived in his family a century after penal servitude, where he fell for the murder of a hated German manager. Savely told Matrona what Russian heroism is: a peasant cannot be defeated, because he "bends and does not break."

The birth of the first-born Demushka brightened the life of Matryona. But soon the mother-in-law forbade her to take the child into the field, and the old grandfather Savely did not keep track of the baby and fed him to the pigs. In front of Matryona, the judges who arrived from the city performed an autopsy of her child. Matrena could not forget her first child, although after she had five sons. One of them, the shepherdess Fedot, once allowed a she-wolf to carry a sheep. Matrena accepted the punishment assigned to her son. Then, being the pregnant son of Liodor, she was forced to go to the city to seek justice: her husband was taken into the soldiers bypassing the laws. The governor Elena Aleksandrovna helped Matrena then, for which the whole family is now praying.

By all peasant standards, Matrena Korchagina’s life can be considered happy. But it is impossible to tell about the invisible spiritual thunderstorm that has passed through this woman - as well as about unpaid mortal insults, and about the blood of the first-born. Matrena Timofeevna is convinced that the Russian peasant woman cannot be happy at all, because the keys to her happiness and free will are lost by God himself.

In the midst of haymaking, wanderers come to the Volga. Here they witness a strange scene. In three boats, a noble family swims to the shore. The pigs, who had just sat down to rest, immediately jump up to show the old master their zeal. It turns out that the peasants of the village of Vakhlachina help the heirs to hide the abolition of serfdom from the landowner Utyatin who has survived from his mind. Relatives of Posledysh-Utyatin for this promise the peasants floodplain meadows. But after the long-awaited death of Posledysh, the heirs forget their promises, and the whole peasant performance turns out to be in vain.

Here, near the village of Vakhlachina, wanderers listen to peasant songs - corvée, hungry, soldiers, salty - and stories about serfdom. One of these stories is about the serf of an approximate Jacob the faithful. Jacob's only joy was the satisfaction of his master, the small landowner Polivanov. Samodur Polivanov in gratitude beat Jacob in the teeth with his heel, which aroused even greater love in the footman's soul. By old age, Polivanov lost his legs, and Yakov began to follow him as if he were a child. But when Jacob's nephew, Grisha, decided to marry the fortress beauty Arisha, Polivanov out of jealousy gave the guy to recruit. Jacob was washed down, but soon returned to the master. And yet he managed to take revenge on Polivanov - the only way available to him, the lackey. Having brought the master into the forest, Jacob hanged himself directly above him on a pine tree. Polivanov spent the night under the corpse of his faithful slave, moaning horror to drive away birds and wolves.

Another story - about two great sinners - is told to peasants by God's wanderer Jonah Lyapushkin. The Lord awakened the conscience of the chieftain of the robbers of Kudeyar. The robber took away the sins for a long time, but all of them were released to him only after he killed the cruel gentleman Glukhovsky in a fit of anger.

The peasant wanderers also listen to the story of another sinner - the Gleb the elder, who, for money, hid the last will of the late admiral-widower, who decided to free his peasants.

But not only peasant wanderers think of national happiness. In Vakhlachin lives the son of a clerk, seminarist Grisha Dobrosklonov. In his heart, love for the deceased mother merged with love for the whole Vakhlachina. For fifteen years, Grisha had firmly known to whom he was ready to give his life, for whom he was ready to die. He thinks of the whole mysterious Russia as a wretched, abundant, powerful and powerless mother, and expects that she will have the same indestructible power that he feels in his own soul. Such strong souls as those of Grisha Dobrosklonov, the angel of mercy himself calls on a fair path. Fate prepares Grisha "a glorious path, the name of a loud protector, consumption and Siberia."

If the peasant wanderers knew what was going on in the soul of Grisha Dobrosklonov, they would probably understand that they could already return under their native shelter, because the purpose of their journey was achieved.

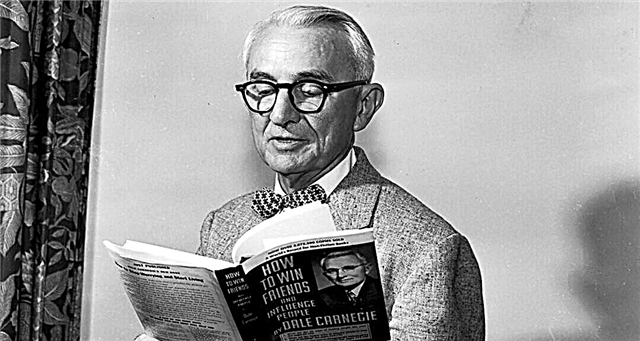

How to solve the five main problems of the team

How to solve the five main problems of the team