: In solitary confinement in the Gestapo, the hero brings to madness a collection of chess games. Freed, he defeats the world champion, the madness returns, and the hero swears never to play again.

Among the passengers of a large ocean boat sailing from New York to Buenos Aires is the world chess champion Mirko Centovich. A more informed friend of the narrator reports that Mirko was orphaned at twelve. A compassionate pastor from a remote Yugoslav village took him into care. The boy was stupid, stubborn, tongue-tied. His clumsy brain did not absorb the simplest things. Mirko’s unusual ability to play chess was discovered by chance. He won many times against the pastor, his neighbor, chess lovers from a neighboring town.

Learning for six months in Vienna from a connoisseur of a chess game, Mirko never learned to play blindly, as he could not remember the previous moves of the game. This flaw did not hinder Mirko’s success. At seventeen, he already had a dozen different prizes, at eighteen he became the champion of Hungary, and at twenty he became the world champion.

The best players, who undoubtedly excelled him in intelligence, imagination and courage, could not resist his iron, cold logic.

At the same time, he remained a limited, uncouth guy. Using his talent and fame, he tried to earn as much money as possible, while showing petty and rude greed. For many months he did not lose a single game.

On the steamboat, the narrator finds chess lovers, among whom the Scotsman Mac Connor, a mining engineer, stands out. Mac Connor belongs to that category of self-confident, prosperous people who perceive any defeat as a blow to their pride. Mac Connor persuades the champion for a substantial fee to give a simultaneous game to a company of chess lovers. The champion suggests that all amateurs play against him together.

This party ends with a complete defeat of lovers. Mac Connor requires revenge. Centovich agrees. On the seventeenth move, a favorable position for amateurs is formed. Mack Connor takes the pawn, when he is stopped by the hand of a man of about forty-five with a narrow, sharply defined, deathly pale face. He predicts the development of the game and our defeat. Players are amazed, because only a top-class player can predict a mate in nine moves.

His sudden appearance, his intervention in the game at the most critical moment seemed to us something supernatural.

Thanks to the advice of a stranger, amateurs achieve a draw with the world champion. Centovich proposes to play the third installment. Having guessed who was his real and only opponent, he looks at the stranger. Embraced by ambitious excitement, Mac Connor insists that the stranger alone play against Centovich, but he refuses and leaves the salon.

The narrator finds a stranger on the upper deck. He appears to be Dr. B. This name belongs to a family respected in old Austria. It turned out that he did not suspect that he had successfully played against the world champion. After hesitating, Dr. B. agrees to a new party, but asks to warn lovers that they do not have too high hopes for his abilities. The narrator is amazed at the accuracy with which the doctor referred to the smallest details of the games played by different champions. Apparently, he devoted a lot of time to studying the theory of a chess game.

Dr. B. agrees with a smile, adding that this happened under exceptional circumstances. He invites the narrator to listen to his story.

Dr. B's story

During the Second World War B.together with his father headed the law office in Vienna. They gave legal advice and managed the property of wealthy monasteries. In addition, the office was entrusted with the capital management of the members of the imperial house.

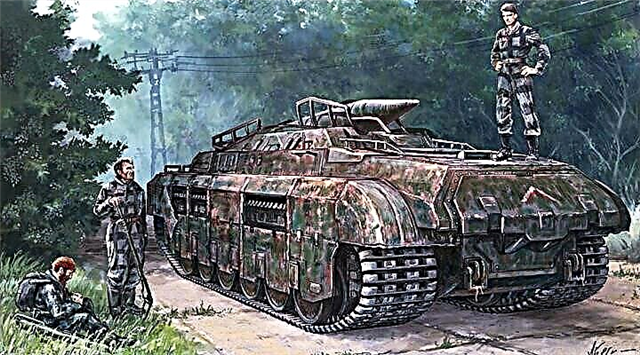

The Gestapo relentlessly followed B. The day before Hitler entered Vienna, the SS men arrested him. B. was included in a group of people from whom the Nazis expected to squeeze money or important information. They were placed in separate rooms of the Metropol Hotel, where the Gestapo headquarters were located. Without resorting to ordinary torture, the Nazis used a more refined torture of complete isolation.

They simply put us in a vacuum, in the void, knowing well that loneliness most affects the human soul. Having completely isolated us from the outside world, they expected that internal tension rather than cold and lashes would force us to speak.

The clock was taken from B., and the windows were laid with bricks so that he could not determine the time of day. For two weeks he lived out of time, out of life. They were called regularly to questions and kept for a long time to wait. Four months later B. waited his turn in front of the investigator's office. There, in a small hallway, overcoats hung. From the pocket of one overcoat he managed to steal a small book and bring it to his room.

The book turned out to be a manual on a chess game, a collection of one hundred and fifty chess games played by major masters. Using a checkered sheet instead of a chessboard, B. made figures from a bread crumb and began to play the games described in the collection.

He played the first game many times, until he completed it without errors. It took six days. After another sixteen days, B. no longer needed a sheet.

By the power of my imagination, I could reproduce a chessboard and pieces in my mind and, thanks to the strict definiteness of the rules, immediately mentally grasped any combination.

Two weeks later B. could play any game from the book blindly. The chess problem book became a weapon with which he could fight against the oppressive monotony of time and space. Gradually B. began to receive aesthetic pleasure from his occupation. This happy time lasted about three months. Then he found himself in a void again. All games were studied dozens of times, and B. had only one way out: to start playing chess with himself. embraced "artificially created schizophrenia,‹ ... ›deliberate bifurcation of consciousness with all its dangerous consequences." During the game he came into a wild excitement, which he himself called "poisoning with chess."

The time came when this obsession began to have a destructive effect not only on B.'s brain, but also on his body. Once he woke up in a hospital with an acute disorder of the nervous system. The attending physician knew B.'s family and told him what had happened. The prison guard heard B.'s screams in the cell, thought that someone had penetrated the prisoner, and entered. As soon as he appeared on the threshold, B. rushed to him with his fists, shouted: “Make a move, a scoundrel, a coward!”, And with such fury he began to strangle him that the guard had to call for help. When B. was dragged for a medical examination, he escaped, tried to throw himself out the window, broke the glass and cut his arm badly, after which there was a scar. In the early days of the hospital, he experienced something like an inflammation of the brain, but soon his mind and centers of perception were completely restored.

The doctor did not inform the Gestapo that B. was completely healthy, and achieved his release.

As soon as I remembered my confinement, an eclipse occurred in my mind, and only many weeks later, in fact, only now, on the ship, I found the courage to realize what I experienced.

B. considers the upcoming party a test for himself. He wants to find out if he can play with a living opponent, and what is the state of his mind after being imprisoned in the Gestapo. He doesn’t intend to touch chess anymore: the doctor warned him that a relapse of “chess fever” is possible.

The next day, B. outright beats the world champion. Centovich requires revenge. Meanwhile, the narrator notices the onset of a bout of quiet insanity at B. On the nineteenth move, he begins to make gross mistakes. The narrator grabs B. by the hand, runs his finger over the scar and utters the only word: “Remember!”. Covered with cold sweat, B. jumps up, recognizes the victory for Chentovich, apologizes to the audience and declares that he will never touch chess again. Then B. bows and leaves "with the same modest and mysterious appearance with which he first appeared among us."

McKinsey Tools

McKinsey Tools